Stewardship is taking responsibility to protect something that we do not own, a relatively new concept that essentially focuses on the management of public goods. Water stewardship is based on the premise that all water users play a role in the sustainable management of water resources, and that a single actor working alone cannot effectively address complex water issues that are often caused by poor water management. Water stewardship approaches are, therefore, based on collective responses.[1] Businesses increasingly realize the need to take responsibility for their role in promoting sustainable water use and management through collective action initiatives to address water related risks in their operations and/or supply chains.

Important activities in the global discourse

Based on the model of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and the Forest Stewardship Council, the European Water Partnership (EWP) and the Alliance for Water Stewardship (AWS) are currently developing global water stewardship standards. This will create the basis for an objective reporting, certification and communication scheme for water stewardship for a broad range of water users and industries. While AWS and EWP are consulting regularly and have formed partnerships, both organisations have separately published a draft standard.[2][3]

The UN Global Compact CEO Water Mandate, launched in July 2007 by the UN Secretary-General, is a unique public-private initiative designed to assist companies in the development, implementation, and disclosure of water sustainability policies and practices. It offers the business case for corporate water stewardship by describing global water challenges and water-related business risks.[4] To guide businesses that want to engage in collective action, the Mandate has released the “Guide to Responsible Business Engagement with Water Policy” and the “Guide to Water-Related Collective Action”.[5] Additionally, it has recently released the “Water Action Hub”, an online platform designed to promote water-related collaboration among business and other stakeholders in watersheds.[6]

GIZ approach

Example 1: Water Futures Partnership

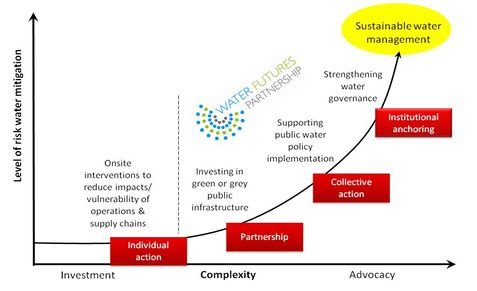

GIZ has applied the water stewardship concept in the Water Futures Partnership. Together with the World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF) and the brewery SABMiller, GIZ initiated the partnership in 2009. Its central aim is to instigate private sector engagement with other actors, including NGOs and government organisations, to address the causes of water risks. The approach is based on the “shared risk paradigm”, which recognises that a single business or community group alone cannot effectively tackle the complex causes of water risks. The founding partners have formed local collective action partnerships in Peru, South Africa, Tanzania, Ukraine and Zambia to address water risks shared by communities, businesses and the environment on a watershed level.

Source: GIZ

From this approach, GIZ has developed the following definition for water stewardship: “Water Stewardship refers to water users taking the responsibility to promote the more sustainable use and management of water in order to reduce their water-related risks. They can only meaningfully do this by a) working to reduce their own impacts on water in the value chain; b) understanding the shared water risks they face on a location specific basis; c) engaging in partnerships and collective action to address these shared water risks.”[7]

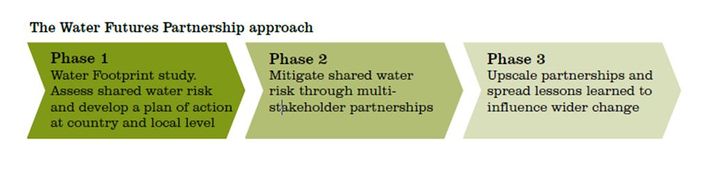

Typically, the local collective action partnerships start with an assessment phase that assesses a) the current state of the watershed, groundwater, infrastructure, water management institutions, water policy, supply and demand etc; b) the risks these generate for the business and surrounding communities and ecosystems; and c) how climate and social change may affect these risks over the next 20 years. Assessing the risks from a financial perspective provides the rationale and evidence base for SABMiller’s businesses to support interventions in water management beyond their breweries or farms. Water risks might include, for example, regional water shortages resulting in an interruption to the brewery water supply, or a polluted water source requiring more costly water treatment.[8]

After the shared risk is exposed and targeted through an action plan, multi-stakeholder partnerships between the local community, the public sector and the company are developed to mitigate the shared water risk in the second phase. These interventions are tailored to the local situation and can include a wide range of projects covering groundwater protection, watershed conservation, infrastructural upgrades and strengthening of local water management institutions.

The third phase then reflects upon the lessons learned from the previous two phases and seeks to include new partners to influence wider change beyond one company. It seeks to attract other partners from the private sector to sustainably influence a more cautious use of water resource in their supply chains.[9]

Transforming to a broader initiative to up-scale the approach, the Water Futures Partnership is now opening up to incorporate new partners and countries.[10]

Example 2: Sasol- Emfuleni-GIZ partnership in South Africa

The Emfuleni Local Municipality (ELM) experiences annual water losses of 44%, that is 36 million m³. Many municipalities, including Emfuleni, do not have the necessary capacity, instruments or resources to implement the required water conservation and demand management actions. This not only threatens the water supply of the residents, but also poses water risks to business and contributes to restricted economic development.

Businesses are set demanding water-reduction targets by the government, but in many cases have already made significant investments to reduce their water use. They now face the law of diminishing returns: it costs an increasingly large amount to make further, relatively small, water savings.

A pioneering development partnership between GIZ, Sasol New Energy Holdings (Pty) Ltd. and the ELM is developing a mechanism to enable a large industrial water user to redirect its water efficiency investments “offsite”, i.e. to help save significantly more water in an upstream municipality. This will allow the industry to offset its own water use and help to secure its future water supply, while the upstream municipality benefits from reduced raw water costs, reduced pumping costs and overall increased water security for its residents. Such a partnership will thus demonstrate how a public-private sector cooperation model can be established to incentivise and leverage private investment into public water infrastructure and into the capacity of municipal service providers, to reduce urban water demand and shared water risks.

The Sasol-Emfuleni-GIZ partnership focuses on initiatives to reduce physical water losses in prioritised areas; on education and awareness of the community regarding water conservation issues; and on the development of new or support of existing community plumbing entities.

Right from the beginning, the savings in drinking water and energy costs will be re-invested to augment the partnership seed funding from German Development Cooperation and Sasol and to initiate new water conservation interventions.

A projected key result is the reduction of water losses in the ELM area by 12 million m³ by June 2014. A decline of physical water losses, as well as financial losses (theft, inaccurate metering, and bill collection), across the system is also anticipated, thereby improving the municipality’s financial situation. Over and above the direct benefits for ELM, positive results are envisaged in respect of job creation in water-related services.[11]

References

- ↑ Alliance for water stewardship: http://www.allianceforwaterstewardship.org/about-aws.html#what-is-water-stewardship [2013-02-18].

- ↑ European Water Partnership (EWP): European Water Stewardship standard. http://www.ewp.eu/activities/water-stewardship/water-stewardship-standard/ [2013-02-18].

- ↑ Alliance for Water Stewardship: Water Stewardship Standard. http://www.allianceforwaterstewardship.org/what-we-do.html#water-stewardship-standard [2013-02-18].

- ↑ The CEO Water Mandate by the UN Global Compact: http://ceowatermandate.org/about/ [2013-02-18].

- ↑ The CEO Water Mandate (2012): Guide to Water-Related Collective Action. http://pacinst.org/reports/water_related_collective_action/wrca_full_report.pdf

[2013-02-18].

- ↑ The CEO Water Mandate: Water Action Hub. http://ceowatermandate.org/2012/08/29/ceo-water-mandate-launches-global-water-action-hub/ [2013-02-18].

- ↑ GIZ 2011: Shared Water - South Africa. http://www.giz.de/Themen/de/dokumente/giz2011-en-south-africa-psb-sasol-emfuleni.pdf [2013-02-18].

- ↑ Water futures partnerships: http://www.water-futures.org [2013-02-18].

- ↑ SABMiller plc, GIZ and

WWF-UK (2011): Water Futures. Addressing shared water challenges through collective action. http://www.water-futures.org/fileadmin/user_upload/PDF/2011_Water_Futures_Report.pdf [2013-02-18].

- ↑ Water future partnerships: http://www.water-futures.org/about/next-steps.html [2013-02-18].

- ↑ GIZ (2011): Shared Water - South Africa. http://www.giz.de/Themen/de/dokumente/giz2011-en-south-africa-psb-sasol-emfuleni.pdf [2013-02-18].