|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| | | | |

| − | For better understanding the interdependencies between natural resource systems and human development and well-being, special attention should be paid to the challenging concept of Ecosystem Services and the importance of an approach for their valuation. As defined by many scholars and by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from nature (MA 2005). Many of these benefits are quite easy to observe and to quantify like production services such as crops or livestock. Other ecosystem services such as climate change mitigation, flood and erosion control or water regulation and purification are difficult to detect and therefor they are undervalued or not considered in decision making processes or policy change. The costs of losses in those ecosystem services can go mostly unnoticed. The main reasons behind this fact are the missing awareness of decision makers and resource managers about the true value of natural capital, and the lack of indicators and market prices. | + | For better understanding the interdependencies between natural resource systems and human development and well-being, special attention should be paid to the challenging concept of [[Ecosystem_services_approach|Ecosystem Services]] and the importance of an approach for their valuation. As defined by many scholars and by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from nature (MA 2005). Many of these benefits are quite easy to observe and to quantify like production services such as crops or livestock. Other ecosystem services such as climate change mitigation, [[Flood_protection|flood]] and [[Anti-erosion_measures|erosion control]] or water regulation and purification are difficult to detect and therefor they are undervalued or not considered in [[Decision-making_support|decision making processes]] or policy change. The costs of losses in those ecosystem services can go mostly unnoticed. The main reasons behind this fact are the missing awareness of decision makers and resource managers about the true value of natural capital, and the lack of indicators and market prices. |

| | | | |

| | Given the high values, and the diversity, of ecosystem services provided by intact wetlands, and that a large proportion of these values are from water-related regulation services such as water flow regulation, moderation of extreme events and water purification, the widespread and major losses of all types of inland and coastal wetlands have inevitably already led to a progressively increasing major loss of wetland ecosystem services value delivery to people. Permitting the remaining wetlands be converted or letting them degrade, means further loss of their value to people. Such costs of inaction (or action to convert wetlands) can be very high (TEEB 2013). | | Given the high values, and the diversity, of ecosystem services provided by intact wetlands, and that a large proportion of these values are from water-related regulation services such as water flow regulation, moderation of extreme events and water purification, the widespread and major losses of all types of inland and coastal wetlands have inevitably already led to a progressively increasing major loss of wetland ecosystem services value delivery to people. Permitting the remaining wetlands be converted or letting them degrade, means further loss of their value to people. Such costs of inaction (or action to convert wetlands) can be very high (TEEB 2013). |

Revision as of 17:12, 1 March 2014

For better understanding the interdependencies between natural resource systems and human development and well-being, special attention should be paid to the challenging concept of Ecosystem Services and the importance of an approach for their valuation. As defined by many scholars and by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from nature (MA 2005). Many of these benefits are quite easy to observe and to quantify like production services such as crops or livestock. Other ecosystem services such as climate change mitigation, flood and erosion control or water regulation and purification are difficult to detect and therefor they are undervalued or not considered in decision making processes or policy change. The costs of losses in those ecosystem services can go mostly unnoticed. The main reasons behind this fact are the missing awareness of decision makers and resource managers about the true value of natural capital, and the lack of indicators and market prices.

Given the high values, and the diversity, of ecosystem services provided by intact wetlands, and that a large proportion of these values are from water-related regulation services such as water flow regulation, moderation of extreme events and water purification, the widespread and major losses of all types of inland and coastal wetlands have inevitably already led to a progressively increasing major loss of wetland ecosystem services value delivery to people. Permitting the remaining wetlands be converted or letting them degrade, means further loss of their value to people. Such costs of inaction (or action to convert wetlands) can be very high (TEEB 2013).

Rationale

To improve access to water resources many programs have been developed, but they have not given adequate consideration to harmful trade-offs with other services provided by wetlands. Many conversions of wetlands have favoured provisioning services (mainly food production) at the expense of losing or reducing delivery of regulation and supporting services (MA 2005).

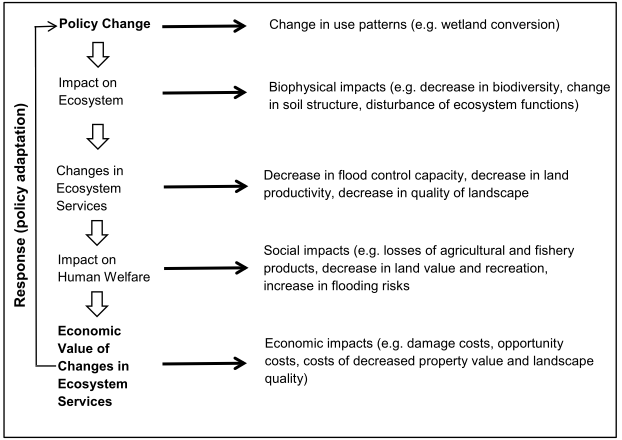

When wetlands are converted or degraded a cost can be incurred by society if the ecosystem services that were previously provided (at no cost) by wetlands may be needed to be replaced by building infrastructures such as water treatment plants. Examples of increased cost are: illness and health care costs (water contamination); infrastructure costs such as costs for construction, operation, maintenance, and monitoring; threats to biodiversity and increased carbon emission; decreased property value of the land due to the degraded aesthetic qualities; decreased recreational opportunities; increased insurance costs due to the high flooding risks; and the decreased income from tourism activities associated with healthy ecosystems. Indeed identifying, understanding, and valuating these services provided by wetlands can lead to well sound decision making, and avoid unexpected or unintended impacts from development decisions or policy changes. Figure 1 illustrates the scientific evidence of an ecosystem services approach and the valuation sequences.

Figure 1: The pathway from policy change to socio-economic impacts

Source: own illustration based on TEEB (2009)

Many empirical studies on valuating different ecosystems services in different regions in the world have been conducted. They helped revealing the relative importance of several ecosystem services especially those, which are not traded in conventional market such as the regulating services. For example the economic assessment of the ecosystem services provided by a coastal wetland in North Sri Lanka (Emerton and Kekulandala 2003) revealed the most substantial benefits that accrue to a wide group of the population as well as to economic actors are related to the regulating services such as the flood preventing capacity of the native wetland (1907 US$ per hectare and year) and the industrial and domestic wastewater treatment (654 US$ per hectare and year), whereas the several provisioning services such as agriculture, fishing and firewood, which directly contributed to the local income presented only 150 US$ per hectare and year. Coastal wetlands in the USA are estimated to currently provide US$ 23.2 billion per year in storm protection services alone, whereas large areas of such wetlands have already been lost. A loss of one hectare of those wetlands is estimated to correspond to an average increase in storm damage of about US$ 33,000 (Constanze et al. 2008).

Decision makers as well as resource managers are therefore asked to recognize the full suite of environmental, cultural and socio-economic benefits from wetland restoration, as the failure to recognize these multiple benefits often undermines the rationale for wetland restoration and compromises future well-being (Alexander and McInnes 2012).

Operationalization of the approach

Recognizing the values of wetlands in the case study area needs: firstly, assessing the dependence on ecosystem services for social, economic and human well-being; secondly, identifying the benefits received from the ecosystem services (Figure 2); and lastly, determining where those services are generated on the landscape and what are the main drivers (human, natural or policy drivers) that could impact them. The linkage between social, economic and environmental outcomes will help to demonstrate the society’s dependence on the provided ecosystem services. Furthermore, it addresses the trade-offs among current uses of wetland resources, and between current and future uses (MA 2005).

Figure 2: Framework for linking ecosystems to human well-being

Source: De Groot et al. (2010)

Over the last three decades, the decision makers on the island Djerba ignored these types of ecosystem services. Consequently, the mass tourism development induced the increasing urban economic infrastructure that has had negative impacts on the coastal wetlands and their associated services. On the one hand, the drainage of large parts of the insular wetlands for construction purposes impacts coastal communities, both directly by limiting their opportunities for recreation and generating incomes from collecting shellfish, and indirectly by increasing flooding risks. On the other hand, sand extraction from beaches as well as uprooting palms and olive trees, which constitute an integral part of the coastal ecosystem impact both, provisioning services (losses in agricultural production and genetic resources) and regulation services (losses in erosion control capacity). Indeed identifying, understanding, and valuating these services provided by the coastal wetlands can help decision makers to avoid unexpected or unintended impacts from future development decisions on the island.

A challenging concept for identifying ecosystem service opportunities for ecosystem management, which should be applied, is the TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity) six-step approach. It focuses on: (1) specifying and agreeing with the stakeholders on the problem to be addressed, which could emerge for example from a change in policy; (2) identifying the most relevant ecosystem services in relation to the decision to be made; (3) identifying the needed information and selecting the appropriate methods, in accordance with the design of the case study; (4) assessing the expected changes in availability and distribution of ecosystem services; (5) identifying and appraising policy options based on the analysis of expected changes in ecosystem services; and (6) assessing social and environmental impacts of policy options, as changes in ecosystem services affect people differently (TEEB 2013).

An improved understanding of the ecosystem functions and the flow of ecosystem services leads in general to a better management of water and wetlands. This could be achieved through better hydrological, biophysical and socio-economic data that meet the requirements of stakeholders and decision makers. Valuating ecosystem services in monetary form could significantly help demonstrate the important role of wetlands in society and economy and thereby enhance their protection, restoration and sustainable use. However, there is no single methodological approach that could reflect all values embedded in water and wetland related ecosystem services. Different approaches and tools can help assess the benefits that flow from water and wetlands by providing different and complementary information, including qualitative, quantitative, spatial and monetary approaches. Therefore, combining bio-physical indicators, monetary valuation and participatory methods is required for getting representative results. The principal techniques for monetary valuation of environmental goods and services as emphasized by Chee (2004) are: (i) Production function analysis; (ii) Replacement/restoration cost technique; (iii) Travel cost method; (iv) Hedonic pricing; and (v) Contingent valuation.

When the focus is to understand the requirements and limits in using an ecosystem services approach following core questions should be addressed:

Which ecosystem services are central on local, regional and national levels, and who depends on it?

- What information decision makers need?

- What are the barriers to using economic assessment of ecosystem services in different types of decision making?

The development and operationalization of an ecosystem services approach for Djerba’s wetlands constitute one part of an interregional study to assess the economic value of wetland benefits in the Arab countries. This pilot project was approved by the Council of Arab Ministers Responsible for the Environment (CAMRE) within the context of the “Muscat Action Plan 2010 – Key issue 2.7”.

References

Alexander, S. and McInnes, R. (2012). The benefits of wetland restoration. Ramsar Scientific and Technical Briefing Note No. 4. Ramsar Convention Secretariat, Gland, Swizerland. 20pp.

Chee, Y. E. (2004). An ecological perspective on the evaluation of ecosystem services. Biological Conservation 129, 549-565.

Constanza, R.; Perez-Maqueo, O.; Martinez, M. L. ; Sutton, P. ; Anderson, S. J. and Mulder, K. (2008). The value of coastal wetlands for hurrican protection. Ambio 37, 241-248.

De Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L. und Willemen (2010). Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecological Complexity 7, 260-272.

Emerton, L. and Kekulandala, L. D. C. B. (2003). Assessment of the Economic Value of Muthurajawela Wetland. Occasional Papers of IUCN Sri Lanka, No. 4.

MA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) (2005). Ecosystem and Human Well-Being: Wetlands and Water Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC.

Ramsar Secretariat (2010). Muscat Action Plan for Wetlands in the Arab Countries. 3_Muscat_ActionPlan-07.10.10.pdf http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/ramsar_40/Attachment 3_Muscat_ActionPlan-07.10.10.pdf ( Last accessed 27.12.2013).

TEEB (2009). The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity. The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity for national and international policy makers. Summary: responding to the value of nature. Welzel + Hardt, Wesseling, Germany.

TEEB (2013). The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity for Water and Wetlands. IEEP, London and Brussels; Ramsar Secretariat, Gland. http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/TEEB/TEEB_Water-Wetlands_Final-Consultation-Draft.pdf (Last accessed 27.12.2013).

Further reading

De Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M. A. and Boumans, R. M. J. (2002). A typology for Classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecological Economics 41, 393-408.

Wilson, M. A. and Howarth, R. B. (2002). Discourse-based valuation of ecosystem services: establishing fair outcomes through group deliberation. Ecological Economics 41, 431-443.

Bateman, I. J.; Mace, G. M.; Fezzi, C.; Atkinson, G. and Turner, K. (2011). Economic analysis for ecosystem services assessments. Environmental and Resource Economics 48, 177-218.

Turner, R. K. and Daily, G. C. (2008). The ecosystem services framework and natural capital conservation. Environmental and Resource Economics 39, 25-35.

Daily, G. C.; Polasky, S.; Goldstein, J.; Kareiva, P. M.; Mooney, H. A.; Pejchar, L.; Ricketts, H, T.; Salzman, J. and Shallenberger, R. (2009). Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 7, 21-28.

Costanza, R.; d´Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S. ; Grasso, M. ; Hannon, B. ; Limburg, K.; Naeem S.; O´Neill, R. V.; Paruelo, J.; Raskin, G. R.; Sutton, P. and van den Belt, M. (1997). The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 253-260